Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul and Gov. JB Pritzker

CHICAGO - Nothing in federal law forces the state of Illinois and city of Chicago to help the federal government detain and deport illegal immigrants - and even if such a law existed, Congress probably can't constitutionally force the state and local governments in Illinois or other states to cooperate with immigration enforcement, a federal judge has ruled.

On July 25, U.S. District Judge Lindsay C. Jenkins sided with Illinois, Chicago and Cook County in tossing a lawsuit brought by the Justice Department seeking to force the state and local governments to comply with federal requests for assistance with immigration enforcement.

In the ruling, Jenkins, an appointee of former President Joe Biden, said federal immigration law places no burden on states to cooperate with requests from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for information about illegal immigrants or for help in detaining them.

Essentially, she said, Illinois and other states are free to ignore ICE and federal immigration law completely, if they wish, under the federalist system of government established under the U.S. Constitution, so long as state and local governments don't actively interfere with federal enforcement actions.

The federal law, Jenkins said, "merely offers States the opportunity to assist in civil immigration enforcement," so, she said, Illinois' sanctuary policies are allowable because the policies "don't make ICE's more difficult; they just don't make it easier."

The ruling lined up with the argument advanced by Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul and other Illinois Democratic officials, asserting that under the U.S. Constitution's 10th Amendment, Illinois and the local governments could effectively thumb their noses at federal immigration agents and complicate federal efforts to locate and remove illegal immigrants.

"... Yes, Illinois's choice may 'frustrate' implementation of 'federal schemes,' like the current federal executive's (President Donald Trump) avowed commitment to conduct the largest mass deportation in American history," the attorney general's office wrote in its March 4 response.

"But this frustration is not obstacle preemption when the Tenth Amendment protects Illinois's sovereign right not to cooperate in the President's schemes."

That filing had come a few weeks after the Justice Department under U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi had filed suit in Chicago federal court.

The lawsuit seeks injunctions against Illinois, Chicago and Cook County to block the state and local governments from continuing to enforce their so-called sanctuary policies.

Those provisions in state law and local ordinances prohibit state and local government agents, including police and correctional officials overseeing state prisons and county jails, from cooperating with federal immigration enforcement.

This includes prohibiting police and correctional officers from honoring requests from immigration agents to hold illegal immigrants convicted of crimes, including violent crimes, until immigration agents can pick them up to remove them from Illinois and the country.

All of the measures were enacted in recent years by Democrats who dominate Springfield and Chicago, with the stated goal of protecting illegal immigrants from deportation.

Some officials, including Gov. JB Pritzker, have claimed to share the goal of removing violent criminals from the country if they are in the U.S. illegally. However, Pritzker has also been among the harshest critics of ramped up immigration enforcement under President Donald Trump, while also refusing to relent on support for the policies barring police from cooperating with immigration agents, even if those agents are seeking to deport violent criminals.

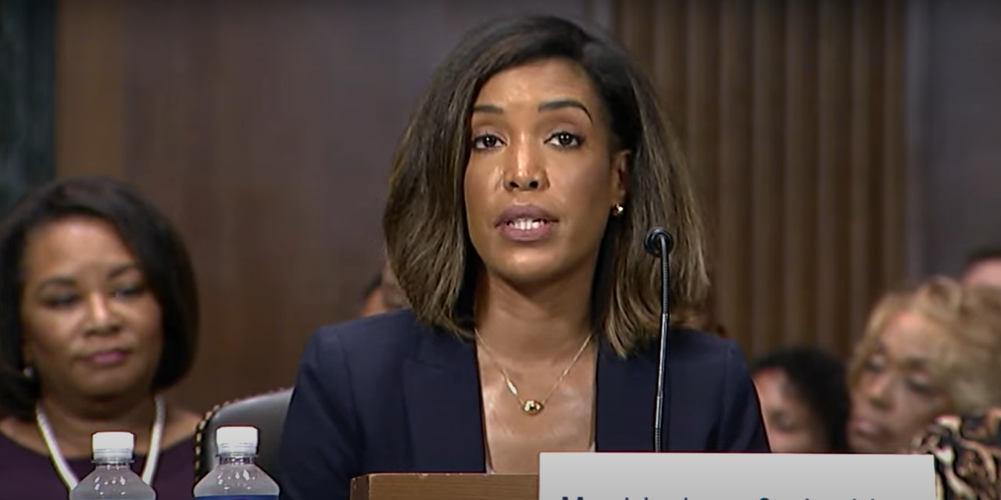

U.S. District Judge Lindsay Jenkins

In the lawsuit, the Justice Department asserts state and local officials are using the sanctuary laws to selectively decide when they are going to cooperate with federal law enforcement.

They said the policies result in Illinois allowing even violent criminals to remain on the streets in Chicago and elsewhere in the state, when they could be easily located and removed, if police were not blocked from cooperating.

The Justice Department asserted the refusal to cooperate amounts to a violation of the so-called Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which establishes federal law as the law of the land when it conflicts with state law.

The Justice Department's lawsuit was supported by the attorneys general of 23 other states. In a brief filed in support, the attorney general of Ohio and others said they believed sanctuary policies in Illinois and other Democratic states effectively incentivize illegal immigrants to enter the country. They said this places a burden on all states, and complicates the federal government's task of enforcing immigration laws, violating the "compact" between the states created when the states ceded control of immigration to the federal government under the U.S. Constitution.

In her decision, Judge Jenkins did not address the states' arguments.

Rather, Jenkins rejected the Justice Department's interpretation of federal immigration law entirely. The judge said she believed the law only requires the federal government to enforce immigration laws and empowers the federal government to request assistance from the states. It does not, however, require states to assist at all.

Further, the judge openly questioned whether the U.S. Constitution would allow any branch of the federal government, including Congress, to issue orders or make laws that could ever state otherwise.

She declined to directly declare unconstitutional laws that appear to direct the states to provide information about people's immigration status. But in her ruling, Jenkins stopped just short of doing so.

While the Constitution permits the federal government to "impose restrictions ... on private actors" - meaning citizens and other individuals in the U.S., as well as businesses and other non-governmental associations and organizations - Jenkins said she believes nothing in the Constitution, under the so-called doctrine of dual sovereignty, empowers Congress to pass laws ordering states and local governments to do anything, including with regard to immigration enforcement.

Jenkins dismissed the lawsuit without prejudice, meaning the Justice Department would have the opportunity to revise their lawsuit to address Jenkins' ruling, if possible, and try again.

The ruling marked the second big legal win Jenkins has delivered for Pritzker and Illinois Democrats on constitutional questions and the limits of state powers in her short time on the federal bench.

In 2023, Jenkins ruled Illinois could ban so-called “assault weapons,” agreeing with Raoul and Pritzker that states don’t violate the Second Amendment by banning weapons, so long as the state determines the weapons to be “particularly dangerous.”