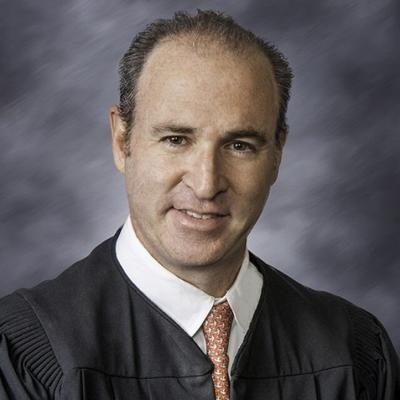

California Supreme Court Justice Joshua Groban

LOS ANGELES - The California Supreme Court has ruled a California law that criminalizes the act of knowingly filing a false misconduct complaint against a police officer is unconstitutional, as the court said the law violates people's constitutional right to free speech.

On Nov. 10, the court ruled 6-1 to strike down the law.

Justice Goodwin Liu was the lone dissenter to the majority's decision.

The case landed in court amid a dispute Los Angeles Police officers and the city of L.A. over the city's move to no longer require people filing a police misconduct complaint to sign a statement affirming that they understood that filing such a report falsely could result in criminal charges.

The dispute over the state law has continued for years.

The law has been on the books for decades, enacted by lawmakers who at the time said they feared law enforcement in the state could be hampered by people filing false complaints against police officers, either out of retribution or a desire to otherwise harm their careers or the administration of the law, bogging police oversight agencies with the need to slog through knowingly false misconduct complaints, while still properly investigating genuine misconduct accusations.

In 2002, the California Supreme Court - with a different set of justices - upheld the law as constitutional. At that time, the court determined the state was allowed to "discriminate" against speech that could be classified under the umbrella of defamation, as it involved knowingly false accusations against police officers.

However, in the years since, federal courts have ruled against the law, particularly determining the state and cities violated the First Amendment by requiring would-be complainants to attest they understand they could be prosecuted for knowingly filing a false complaint against a police officer.

Hit with lawsuits citing those decisions, the city of Los Angeles entered into a so-called "consent decree," under which the city agreed to prohibit police from requiring people to sign the admonition statement. While the consent decree expired in 2013, L.A. has not required such a statement since.

The union representing L.A. Police Department officers sued in 2017, seeking a court order that would force the city to again require such sworn statements from people accusing LAPD officers of alleged misconduct.

In response, the city argued the state law violated the First Amendment speech rights of people accusing officers of misdeeds, regardless of whether the accusations are truthful or concocted.

The Los Angeles Police Protective League prevailed in lower courts, which decided the 2002 ruling, known as People v Stanistreet, still applied, regardless of the federal courts' rulings.

But the city appealed to the California Supreme Court, which ruled against the police officers.

The state Supreme Court majority opinion was authored by Justice Joshua Groban. Chief Justice Patricia Guerrero and justices Carol Corrigan, Leondra Kruger, Kelli Evans and Martin Jenkins concurred in the majority decision.

In the majority opinion, Groban said the court believed it was time to overturn its own earlier ruling, as well as the lower court's decision.

While agreeing people do not have a constitutional right to file potentially career-ending false misconduct complaints against officers, Groban and the majority said the California state law, though "well-intentioned" to protect police officers, still violates the First Amendment because the fear of prosecution might "chill" protected speech by making people hesitate to bring truthful accusations against officers.

The majority said it also believed the law doesn't hold up under the First Amendment because it only criminalizes false accusations against police officers, while providing no threat of criminal prosecution against those who allegedly may lie to protect police officers against misconduct claims.

That, the majority said, means the law unconstitutionally "disfavors" accusations against police officers.

"The question we must ask is whether the average person might be deterred from making even a truthful report of wrongdoing (or at least not a knowingly false one) when they are admonished with the threat of criminal prosecution — and required to sign a document attesting to that admonishment — before they are allowed to complain," Groban wrote for the majority. "We believe the answer to that question is clearly yes."

In his lone dissent, Liu said the majority had gone too far in striking down the law.

He said the state law prohibiting false misconduct reports against police officers is no different than laws making it a crime to file false police reports or commit perjury. Those laws also discriminate against other speech not protected by the First Amendment, Liu noted.

The California law, Liu said, "is compatible with the First Amendment for the same reason that perjury statutes and other laws against false statements in official proceedings have long endured. These laws are of ' ‘unquestioned constitutionality’ ' because they safeguard the integrity of government processes that inform legal judgments or official actions."

And since the challenged California state law specifically says criminal charges can only be sustained against people who "knowingly" bring false accusations against police officers, Liu said the majority provides too little deference to police agencies and prosecutors to decipher when a complaint is knowingly false and when a complaint, filed in good faith, merely turns out to be untrue.

"To be sure, many people, especially members of minority, immigrant, or low-income communities, may be reluctant to file complaints," Liu wrote. "... For police agencies, there is perhaps no task more important than gaining the trust of the communities they serve.

"But trust is a two-way street, and our men and women in uniform have a hard enough job without having to deal with knowingly false allegations of misconduct."

The LAPD officers were represented before the state Supreme Court by attorneys Richard A. Levine and Michael A. Morguess, of the firm of Rains Lucia Stern St. Phalle & Silver, of Encino and Santa Monica.

The city of L.A. was supported in the case by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), among others.

The ruling marked the second time in less than a week that the state high court has weighed in on the question of whether a state law violates the First Amendment by criminalizing certain speech.

In a Nov. 6 decision, the California Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment's free speech guarantees don't prevent the state from potentially criminally prosecuting nursing home workers for willfully and knowingly "misgendering" transgender patients in their long term care facilities.

In that ruling, the unanimous state high court reasoned that the law was akin to workplace anti-discrimination laws which, the court said, criminalize discriminatory conduct, not speech. Essentially, the majority said, nursing home workers could be fined and potentially jailed for up to a year for what they had done, and not what they said.