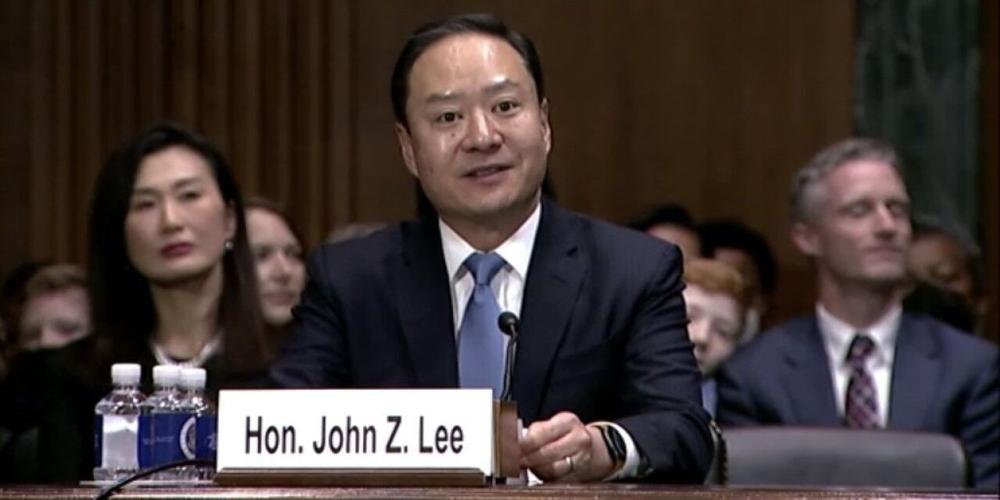

U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Judge John Z. Lee

CHICAGO - A Biden-appointed Chicago federal judge went too far in using a deal struck between the Biden administration and pro-immigrant activists to issue a sweeping order requiring immigration enforcement agents to release hundreds of illegal immigrants arrested and detained earlier this year in and around Chicago in operations ordered by President Donald Trump.

That was the general consensus of a three-judge panel of the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, in a decision addressing the Trump administration's appeal of the order from U.S. District Judge Jeffrey Cummings.

However, in the 2-1 decision, the panel sharply differed on just where the legal line lay that Cummings should have respected.

On one hand, Seventh Circuit judges John Z. Lee and Doris Pryor - who were both appointed to the court by former President Joe Biden - said they believed the so-called consent decree negotiated by the former president, which sought to enshrine the Biden administration's notoriously lax immigration enforcement policies, can be used to bind some of the immigration enforcement policy decisions of the current White House.

But they said in this instance, Judge Cummings overextended the decree to agree with activists that federal agents under Trump had allegedly illegally detained illegal immigrants without warrants.

In their ruling, Lee and Pryor agreed with the Trump administration that Cummings had improperly applied the consent decree, which was centered on one section of federal immigration law that covered so-called "warrantless arrests" of illegal immigrants made during raids and patrols, to also forbid arrests and detentions using different provisions of federal immigration law. Those other provisions specifically allow for immigration agents to arrest illegal immigrants using so-called "field warrants."

In their ruling, Lee and Pryor said Cummings then improperly lumped all of the detained illegal immigrants into one "class," and then ordered all released, without any individual determination on whether their arrest and detention had been proper.

While they said the Biden-era decree can be enforced, the majority said the Trump administration was still likely to prevail on their claims Cummings had illegally used the decree to order the release of perhaps half of the illegal immigrants agents had detained using field warrants.

In dissent, however, Seventh Circuit Judge Thomas Kirsch - who was appointed to the court during the first term of President Donald Trump - said the majority had "tied itself in knots" to uphold at least a portion of Cummings' ruling and dance around the question of whether a prior presidential administration can constitutionally use such consent decrees to forever impose their preferred policy choices on the country, regardless of the desired policies of future democratically elected presidents.

"The majority and the district court ignore these concerns in favor of the policy preferences of the last administration," Kirsch wrote in his dissent.

Kirsch said he believed the court should have granted the White House's request to block Cummings' order entirely.

The case had landed before the Seventh Circuit in November, when the Justice Department appealed Cummings' order.

In that Nov. 13 order, Cummings had directed U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to release more than 600 immigrants arrested and detained under ICE's Operation Midway Blitz immigration enforcement initiative on bond and instead refer them to the government's so-called "Alternatives to Detention" (ATD) program.

The ATD program has been in place since 2004 and, according to past accounts from the federal government, provides a path for immigrants who may be subject to deportation to remain in a local community, rather than in federal custody, while they wait on their immigration proceedings to play out.

Additionally, Cummings ordered 13 immigrants in ICE custody to be released immediately, as the judge said the government agreed those people had been arrested and detained improperly, allegedly in violation of the Biden consent decree.

That deal had ended a class action lawsuit brought first in 2018 on behalf of illegal immigrants who activists and their attorneys claimed had been wrongfully detained and deported by ICE without first securing proper "targeted warrants" clearly identifying the individuals ICE wished to arrest and deport.

While the lawsuit had been filed against ICE during Trump's first term in office, it continued after his departure. And in 2022, the Biden administration struck a deal with their political allies.

After he took office in 2021, Biden promptly reversed a wide range of Trump administration policies, notably including Trump's more stringent approach to immigration enforcement.

According to estimates published by the Migration Policy Institute, federal Department of Homeland Security data showed at least 5.8 million immigrants were allowed into the U.S. under the Biden administration, either under so-called "asylum" status or without any kind of authorization.

Other sources place that number far higher, with some estimating 10 million illegal immigrants or more who entered the U.S. from 2021-2024.

In 2022, the Biden administration agreed to settle the class action on behalf of illegal immigrants in Chicago federal court, further curtailing enforcement actions to locate, arrest and deport illegal immigrants.

Among other terms, the settlement agreement essentially forbade ICE from conducting "raids," but rather generally limiting ICE to making arrests and deportations only in cases in which the agency first obtained targeted warrants against specific individuals the agency believes may be in the U.S. illegally or when officers can document probable cause for making a stop and detention.

That agreement further included a provision which would allow the so-called "consent decree" to be reactivated whenever immigration rights activists believe ICE may no longer be following the procedures required in the decree.

Amid ramped up immigration enforcement actions in Chicago and elsewhere, immigration activists, including the National Immigrant Justice Center and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), then used that provision to reopen the case and persuade Cummings to again order ICE, now once again under Trump, to comply with the agreement reached by his predecessor.

Following Cummings' ruling, the Justice Department asked the Seventh Circuit to stay the ruling while the larger case plays out, saying releasing all of the hundreds of illegal immigrants covered by the ruling would endanger public safety and jeopardize the ability of ICE to carry out its lawful enforcement operations.

U.S. Seventh Circuit Judge Thomas Kirsch

In the Seventh Circuit, Kirsch during oral arguments expressed deep concerns with the scope and substance of Cummings' order.

Those concerns manifested again in his dissent, as he said the majority failed to deal with Cummings' mishandling of the matter.

Kirsch particularly faulted his colleagues for brushing aside constitutional concerns surrounding the use of such consent decrees by one administration to chain successors to their preferred policies.

Kirsch said his colleagues' determination does not "allow maximum room for democratic governance."

"Through a consent decree, one branch of the federal government (the executive) handed over to another (the judiciary) the power to enforce compliance with part of the nation’s immigration laws," Kirsch wrote.

"... Were this consent decree between two private parties, the choice to interpret and enforce the agreement in this way might have been appropriate. But this consent decree isn’t between two private parties. Temporary officeholders of the executive branch—not the United States itself—entered into the agreement.

"Enforcing the promises of those elected officials requires an awareness that '[t]oday’s lawmakers have just as much power to set public policy as did their predecessors,' and that 'democracy does not permit public officials to bind the polity forever.'"

In those passages, Kirsch quoted from an earlier decision, also issued by the Seventh Circuit, which undid consent decrees entered in federal court, which federal judges had used for decades to oversee and review hiring decisions in Cook County and Illinois state agencies and offices, to fight corruption.

Those consent decrees had been opposed by Illinois Democrats in recent years because they argued the decrees allowed the courts to unconstitutionally trespass overlong on the constitutional authority of state and local governments.

In response, Lee and Pryor agreed Cummings' use of the consent decree could raise constitutional questions.

But they brushed Kirsch's concerns aside nontheless, asserting they had no obligation to consider such constitutional issues because they believed the Justice Department failed to raise those constitutional concerns before Judge Cummings and on appeal.

Kirsch scoffed at his colleagues' apparent nonchalance, noting the Justice Department had argued in its appeal that Cummings' order would "interfere with the Executive's immigration enforcement operations." Kirsch said that should have been read as a clear invocation of the separation of powers doctrine, without using the words "separation of powers."

"The government raised this argument in general terms, and—given its significance—we should confront the constitutional dimensions of this case," Kirsch wrote.

The Seventh Circuit panel agreed to pause enforcement of their ruling and Cummings' orders to give the White House 14 days to seek emergency relief from the U.S. Supreme Court.